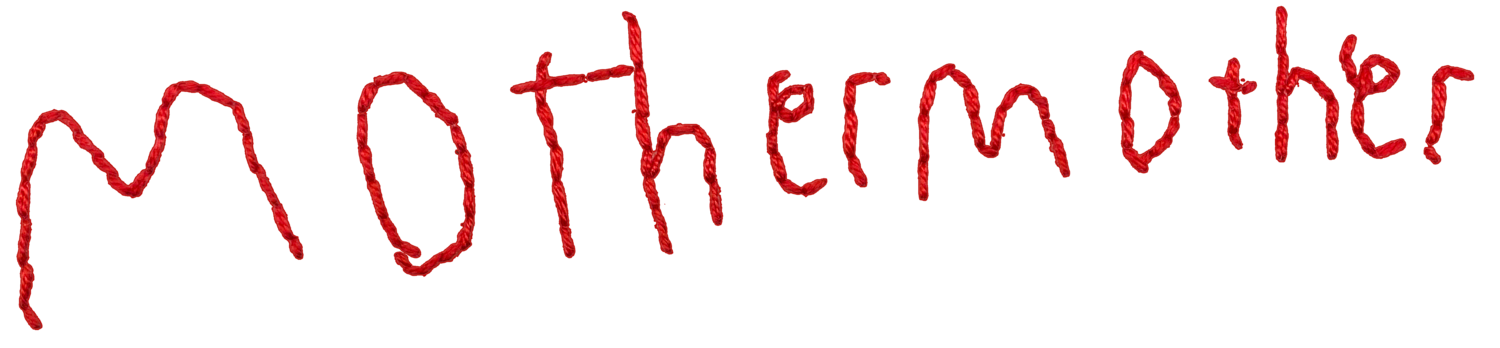

Unifying Threads

8 May - 9 June, 2025 Te Atamira, Remarkables Park, 12 Hawthorne Drive, Frankton, Queenstown

Unifying Threads presented by the mothermother collective explores visual and social expressions of patterns of connection, as they support one of their own moving to and connecting with a new community. For Tori Beeche her relocation to Queenstown prompted feelings of being untethered from her new home. Discussing this with the collective, we realised we are tethered through threads of connection that weave patterns through a community.

Art is a medium of experience that represents our perception of the world around us. In Unifying Threads artists from the mothermother collective consider how they portray their experience of the world in their respective art practices. Collectively they have multiple and varied modes of perception through which they filter their experience of the world. Yet, there is always a unifying thread that connects these practitioners in recognisable patterns of understanding.

Threads of narrative, ecology, weaving, cyclical time, seasons, generations, and journeys are found. For the artists in this exhibition perception is triggered by more than mere sensation, perception occurs when there is recognition of a pattern within the sensuous.

Humxns use order to help us make sense of the physical as well as the metaphysical world and have found patterns everywhere from time immemorial. Recognition for the French critic and theorist Charles Baudelaire (b.1821, d.1867) is about capturing the permanent from the transient. That which stands up to flux and change.

It is through understanding the patterns of connection that we create in our environment that we recognise that we are at home in the world. These bonds form patterns of connection that traverse the behavioural, social, political and geographical landscape.

They are the Unifying Threads that hold us to people and place.

Please see below for Hope Wilson’s text to accompany this iteration.

These vessels

Hope Wilson

May 2025

“If it is a human thing to do to put something you want, because it's useful, edible, or beautiful, into a bag, or a basket, or a bit of rolled bark or leaf, or a net woven of your own hair, or what have you, and then take it home with you, home being another, larger kind of pouch or bag, a container for people, and then later on you take it out and eat it or share it or store it up for winter in a solider container or put it in the medicine bundle or the shrine or the museum, the holy place, the area that contains what is sacred, and then next day you probably do much the same again--if to do that is human, if that's what it takes, then I am a human being after all. Fully, freely, gladly, for the first time.” Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction”

I’m following a line back to December 2024 when I first talked to Nat Tozer about this project, Unifying Threads. We spoke about the strands which are interwoven here at Te Atamira–the work of making a group exhibition, the individual artistic practices of Tori Beeche, Jasmine Clark, Michelle Mayn, Rachel Hope Peary, and Nat Tozer, the process of building connections in a new place, mothermother itself, and how we look after each other. Tozer described mothermother as an artist-run initiative that shares qualities with a net, a social space, and a river. It’s a way of iterating, hosting, connecting, offering reciprocity and working slowly and consistently.

It’s a description that reminds me of a spider weaving and reweaving her web–making and mending her home and her surroundings in relation to the scale and rhythms of her own body. The project title, Unifying Threads, thrums with material and conceptual resonances. Like the vibration of a spider web strummed by a droplet of water. The lines of connection between these artists and their works are drawn through past experiences, familiar landscapes, and shared materials and methods. The opening of this exhibition is an invitation to loop your own line through the warp and weft of their shared understandings.

The beginnings of Unifying Threads were tethered by a group chat. The artists are located across Aotearoa in Kā-Muriwai Arrowtown, Kirikiriroa Hamilton, and Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, and messages flowed back and forth as the works developed. A tide of conversation, rising and falling.

In an early progress photo, the circular centre of Jasmine Clark’s work is photographed floating on the edge of Lake Wakatipu. Anchored on a piece of driftwood, the unwoven ends of the piece starfish out from the base and tickle the light which plays on the surface of the water. Although her work lies flat on the water’s surface, the potential of the form is clear. The piece speaks of containment even as the water rises and falls through the negative spaces of the weaving. In her iconic essay, ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’, Ursula K. Le Guin lists ancestors to the plastic shopping bag: “A leaf a gourd a shell a net a bag a sling a sack a bottle a pot a box a container. A holder. A recipient.” Le Guin’s essay equates these vessels with the form of the novel, writing that a book holds words which bear meanings. Equally, Clark’s strands are inscribed with techniques, patterns, and memories passed down to her by her foremothers. Clark’s work, indeed all the works in Unifying Threads, demonstrates the resilience, story-telling, and pattern-making effort of repetition.

Tori Beeche’s works are also coded with inherited shapes and patterns. Her paintings, oil on linen, offer coy glimpses of imagined and remembered interiors which collage her own memories with her father’s memories of his Norwegian childhood and images drawn from archives. Each composition operates off a grid which is gently delineated by the architecture of the picture space: in one instance the edge of a blue-grey door; in another the batten of a wall or a skirting board; later, a picture frame. Titled according to an established rhythm, each work is first inscribed as ‘Transitive Patterns’ before the reference or homage receives a nod in parentheses. Beeche orbits her own biography, navigating shared and familiar histories which encourage a sense of home-coming and recognition in my own reading of the works.

In late April, Rachel Hope Peary sent a video of her work in progress. The weaving is suspended in the shelter of a porch, open to the fenced section of grass beyond the house. In the video, the expanse of reddened cotton stitching murmurs and breathes in the breeze. In total, the work is two metres in height and seven in length. The dimensions are a personal yardstick, a measure of time spent on arranging, processing, breathing. Writer Lucinda Bennett reflects beautifully of Peary’s process by observing, “These are works that record the unevenness of time, how our hearts do not beat like a metronome, fear and excitement will hasten them and the rhythm will slow when we breathe deep, when we sleep, are unwell, as we age.”

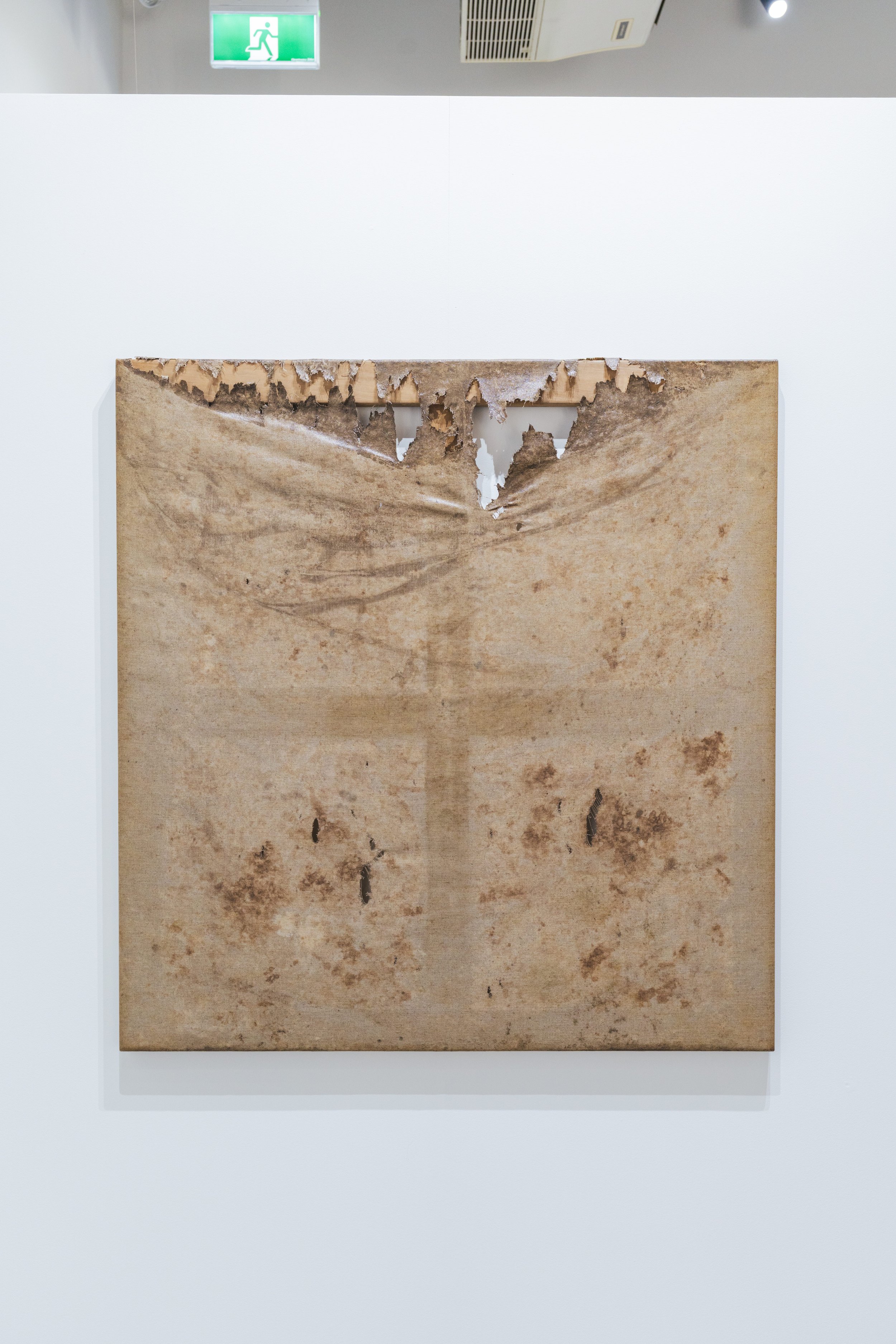

Time is also the maker and the material of Nat Tozer’s work, Observations Of The Ground Through Canvas (on-going). These once-buried canvases map their participation in a life cycle beyond white gallery walls. Arrested mid-decomposition, they attest to the continual existence of an underground conversation between soil, microbes, insects, warmth, and root systems. This chattering, cyclical dialogue continues below our feet. In one late afternoon message, Tori Beeche compares the form of the work to an altarpiece and my memory invokes Mary, Untier of Knots, a once obscure Baroque painting of the Virgin Mary unknotting a long white ribbon. In my mind, she ties, unties, and re-ties the ribbon as it gradually frays and softens to the same tone as Tozer’s unearthed artifacts.

Also in dialogue with the natural environment, Michelle Mayn recounts the journey and arrival of her materials, inaka fibre, gifted by a friend in Ōtautahi Christchurch, and wharariki pods that skeletonised during an extended dye process. She describes both as unexpected gifts and that reminds me of something Tozer mentioned during our December conversation: ‘when you do give, it’s so bizarre, it just comes back.’ Mayn offers her own gifts to visitors–an installation cloaked in white cotton gauze and set in the gallery window where guests can accept homemade guava jelly to take home. Gifting and reciprocity are embedded in the mothermother kaupapa and, accordingly, each artist participating in Unifying Threads acknowledges and honours the relationship between their materials, each other, and the environment. Mayn describes the material resonances of inaka as she shares a work in progress–this long-lived plant can survive over 200 years. She also works with harakeke in her weaving and places wooden reels with hand-twisted, dyed muka in Unifying Threads. Mayn collaborates with and responds to these natural materials by acknowledging their life-force and maintaining a close relationship from beginning to end.

Louise Bourgeois wrote “What is a drawing? It is a secretion, like a thread in a spider’s web ...It is a knitting, a spiral, a spider web and other significant organisations of space.” An exhibition is a significant organisation of space but so is a studio, a garden, a kitchen table, a bedroom. Unifying Threads and mothermother weave together these possibilities by anchoring their intentions in social connection and concern for how we look after each other. Unifying Threads is carried by a current intent on reaching out, breathing, and weaving. Each artist models patterns of repeated and concerted effort–inviting each of us around the next bend of the river.

Foot note

1 This 18th century German painting by Johann Georg Melchior Schmidtner is in the Catholic pilgrimage church of St. Peter am Perlach in Augsburg, Bavaria, Germany. It was popularised first in Latin America and later internationally by Pope Francis.

References

Bennett, Lucinda. “Freedom within the cage.” Laree Payne Gallery, 7 August 2024, https://lareepaynegallery.com/exhibitions/53-the-edges-in-the-middle-a-solo-exhibition-by-rachel-hope-peary/. Accessed 5 May 2025.

Le Guin, Ursula K. “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.” First published in 1986. Still Moving, https://stillmoving.org/resources/the-carrier-bag-theory-of-fiction. Accessed 5 May 2025.

“Louise Bourgeois: Along came a spider.” Art Gallery of NSW, https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/learn/learning-resources/louise-bourgeois/. Accessed 5 May 2025.